THE “APPARENT” DRUG overdose death of drifter Jimmy Mize in a city-owned downtown homeless shelter is a little less apparent today.

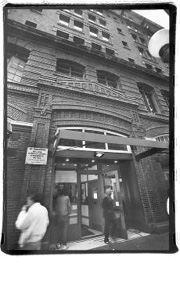

Mize, 45, unemployed, was not a known drug user and no death weapon, i.e., syringe, was found in his messy unlocked flop at the Seattle Housing Authority’s Morrison Hotel on Third Avenue. Even so, police, medical examiners, and city officials found nothing suspicious about his May 7 death.

“Very often,” a deputy medical examiner said, “when we arrive at a crime scene the works [needle] are missing,” supposedly disposed of without a trace by the user or taken by others.

However, a review by this reporter of the other 77 opiate-related deaths reported to the King County Medical Examiner’s office from January to mid-September this year shows only one other case—at a family home in Shoreline—where a needle was not found among the drug paraphernalia at the scene.

The review also shows that in some of the countywide OD cases, fire department medics toss away syringes before the medical examiner’s office arrives, errantly destroying evidence prior to official determination of the cause of death.

Homeless advocates have complained that such deaths sometimes get too little official attention because they involve victims with low social status. In a recent article (“Death of a nobody,” 10/5/00), Seattle Weekly conjectured that Mize’s death could represent a way to perform the perfect murder because of the cursory investigation and ready assumptions in such cases. A housing authority spokesperson called such a theory “innuendo, gossip, and rumor.”

A fellow Morrison resident said he saw Mize the night before in his room and next saw him 21 hours later when he heard Mize’s TV playing, opened his unlocked door, and found him lying on his bed, shirtless and dead.

Police found a rubber tourniquet on the floor, a burned spoon and needle cap on the table, and apparent needle marks on his left arm—everything but the needle itself, which a deputy medical examiner searched for but could not find.

Second-party suspicions are sometimes investigated, however. The review of Medical Examiner records shows a September 8 drug OD death of a 40-year-old man at an Aurora Avenue motel is still open. Even though the death needle was found in that case, suspicions remain because the room had been rented by another man.

THE HOUSING authority, which leaves death probes on its property to police, has little data on its cases. “We do not have a specific record-keeping system that focuses solely on deaths occurring on SHA property,” says SHA attorney Marya Gingrey. The deaths are noted in daily log books, but “these records are not kept in a central location,” she says. The SHA does have a policy on how to dispose of a deceased’s property though, she adds.

Homeless advocates have been especially concerned about crime at the troubled, run-down 91-year-old Morrison, where the city offers free overnight housing for up to 250 people and subsidized temporary housing for another 205 homeless. Drugs have been widely available in the building and around the Pioneer Square neighborhood; although police recently cracked down on dealers in an early-morning roundup witnessed by the police chief and Mayor Paul Schell, with the news media in tow.

A recent city study found 31 of 79 Morrison residents surveyed felt unsafe. Police responded to 158 calls there the first six months of 2000, including 21 assaults, three rapes, and three deaths—one natural and the two apparent drug overdoses.

The review of January-into-September ME records on file at the Seattle-King County Health Department shows that at least 12 homeless men have been found dead downtown from drug overdoses in the Morrison, several privately operated flophouses, and city parks. Additionally, two apparently homeless women died from ODs, one while shooting up in the public restroom at the Westin Hotel, the other overdosing in a restroom at the Nordstrom Rack store. In all these instances in which death was thought to have been from needle-injected drugs, syringes were found in all but Mize’s case.

The Medical Examiner’s office also reports that in April, when an examiner arrived at the overdose death of a homeless man found in a portable toilet in the University District, “the syringes that were found at the scene were discarded by [fire department] medics prior to my arrival.” A similar incident involving county paramedics took place in Covington the previous month at the heroin OD scene of a 41-year-old woman. Medics, a report notes, “found an insulin type syringe and disposed of it before leaving the scene.”

In the January OD death of a 23-year-old Shoreline man—the only other beside Mize’s when a needle was not found among the drug paraphernalia—his body was discovered by a family member, sitting in a chair near a burned spoon and lighter. The missing syringe was not explained by investigators. However, they classified the death, like Mize’s, as an apparent accidental OD.

Seattle police, who did not further investigate Mize’s death after a patrol officer concluded there was “nothing suspicious” about it, have now taken a second look at the request of Chief Gil Kerlikowske. But a police spokesperson last week said “the case was handled correctly and done very well,” even though admitting that “possibilities exist” that others could have been in Mize’s room and involved in his death.