THE WORLD IS a smaller, more dangerous place, say the security experts of our post-Cold War era, but they’re just jealous. While they sit desk-bound in DC, trying to make a plausible new enemy out of Afghanistan, adventuresome tourists are visiting the place. Once we were bombing Vietnam; now we’re mountain biking there. Once Antarctica was the frozen province of Scott and Amundson; now Zodiacs deposit us on its penguin-lined shore. Once only Hillarys and Whittakers climbed Everest; now anyone with $65,000 to spare can make the ascent.

Times have changed for tourism. The whole world’s become an open travel market—with previously remote destinations easily available to those holding enough of that global currency, the almighty US dollar. Nothing’s off limits for those willing and able to pay. The higher the price tag, the more desirable the trip, especially for affluent, educated types who sneer at Disneyland’s masses, towering white cruise ships, and cushy package tours.

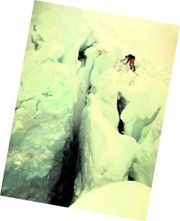

In their place, an entire adventure travel industry has sprung up to cater to a fast-growing clientele. Many of these businesses are located in the outdoors-mad Northwest, and many locals have gone on their treks, climbs, and whitewater rafting expeditions. Some have also died. Several have been injured. Many have been sick, scared, or lost—yet, wallets in hand, they keep coming back for more.

Indeed, the adventure travel biz is thriving in part by selling the image of danger, with some high-profile accidents ironically serving as marketing tools. (As many attest, Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer’s first-person Everest disaster account, has had an effect far beyond climbing circles.) At the same time, the long-boom economy has produced unprecedented demand for such out-of-the-way excursions, with knowledgeable, moneyed customers eager and able to pay with a single click of the mouse. The result is a cycle of spending and exploring that already has Seattle companies sending its clients to the bottom of the ocean and the top of the world.

Rupees and baht

The adventure travel business amounted to some $230 billion in 1998, according to generous estimates by the Colorado-based Adventure Travel Society. Of that spending (which includes equipment, food, airfare, etc.), roughly $100 billion went to guides, outfitters, and companies—which the ATS claims represents some 20 percent of overall US travel outlays in all categories (collectively worth $541 billion). Half of all Americans had taken an adventure travel holiday during the prior five years, according to a 1997 survey by the Travel Industry Association of America. The TIA also estimates that adventure travelers spend an average of $395 per day on such excursions (on a median basis), which is considerably more than your run-of-the-mill package tour. The same survey reveals that—baby boomer image notwithstanding—64 percent of adventure travelers are classified Gen X.

Moreover, “adventure travel” itself is a somewhat elastic classification, encompassing scuba diving to hunting to guided climbing to watching lions from the comfort and security of a chauffeured Land Rover. Yet none of those activities come cheap. Excluding taxes and airfare, your average foreign trekking itinerary runs around $3,000. Extreme elements add more to the bill. Climbing Aconcagua or Kilimanjaro runs about $4,000 on expeditions organized by Seattle’s Alpine Ascents. The bill hits $23,000 for Antarctica’s Mt. Vinson, one of the prized seven summits (each being the highest peak on its continent).

If altitude sickness and frostbite aren’t your bag, how about cycling through Vietnam with REI Adventures ($3,045), hiking Peru’s Inca trail ($2,390), or sea kayaking off Baja ($1,195)? Closer to home, Seattle’s woman-oriented Adventure Associates will take you skiing in Yellowstone for $1,595. A three-day weekend with Mazama’s North Cascades Heli-Skiing runs up to $2,425. In what the industry calls the “soft” spectrum of adventure travel, Seattle’s Zegrahm Expeditions will give you the full tour of Patagonia for $6,850 or retrace the Alaskan coastal voyage of the 1899 Harriman expedition—we don’t know who he was, either—for $6,990.

Who can pay for such trips? Plenty of people. “It used to be doctors and lawyers,” says Alpine Ascents’ Matt Lepisto of his mountain climbing clients. Now, in our dot-com era, many other professionals are entering the thin air of affluence. “It’s certainly changing to a more broad and general segment of the population. We fall into the higher end of the disposable income type of market,” he adds. Accordingly, his company can afford to gear its rates—and goals—to niche customers eager to trade their wing tips for crampons. Meanwhile, competitors flock to grab a share of the alpine guiding business. “Half the companies out there weren’t therefour years ago.”

Indeed, the ATS boasts that adventure travel is “the fastest growing segment of the travel industry.” It says there’s been 8 percent to 10 percent growth annually over the past decade. (The more conservative TIA has tracked 5 percent to 6 percent increases over the same span.) Why the boom? Beyond consumer prosperity and curiosity, ATS president Jerry Mallett says, “We’re definitely media-driven.” He points to the proliferation of books, TV shows, and magazines glorifying once-remote regions. “The publications both feed and benefit from it,” he notes, naturally citing Into Thin Air as well as A River Runs Through It (both the book and the movie), which created a surge of interest in fly-fishing vacations, especially among women. Thinking back to the ’70s, he recalls a similar consumer effect from the film Deliverance. “Everyone wanted to do it!” he says of whitewater paddling. The irony that that movie, like Krakauer’s book, detailed death and disaster in the outdoors is not lost on him. Does such notoriety paradoxically benefit the adventure travel biz? “I think it does,” Mallett concludes.

The money trail

No other leisure time business has such an inverse relationship to death. After Duvall resident Luan Phi Dawson was killed at Disneyland in December ’98 by a flying metal boat cleat, the theme park quickly cleaned up the blood and quieted any subsequent mention of the accident. Compare that to the equally sad demise of Renton postman Douglas Hansen in the Everest storm of May ’96. Both men were at the wrong place at the wrong time, but the latter’s death—along with six others—helped launch unprecedented interest in all things Everest.

As a result, trekking to the Solu Khumbu region of Nepal has grown even more popular. “I definitely think that it really sparked an interest in people who [read] that to see Nepal and to see the mountains,” says Cynthia Dunbar of REI Adventures regarding Into Thin Air. “Travel is really cyclical; the media play an extremely important role,” she adds. Offering some 70 different trips last year, REI appears to be the biggest adventure travel operator in the Northwest. Even if the firm isn’t guiding clients up 8,000 meter peaks, the spillover effect draws still more sojourners to the well-trodden Everest approach route. (REI’s package costs about $3,000; others run higher.)

Part of the lure of such trips, notes Trekking in Nepal author Dr. Stephen Bezruchka, is the faint whiff of danger they provide. “It is in our nature to take risks, and different sectors of society do it in different ways,” he says. As a practical matter, automobile wrecks and intestinal diseases are the greatest threat to Himalayan trekkers, he adds. Of course, those aren’t the headlines that draw affluent adventure travelers abroad. It’s glory, not dysentery, they’re after. They’re not content with armchair expeditions. Once it was enough to read about the accomplishments of Peary, Mallory, or Shipton; now they want to do what those men did, to follow in their footsteps, retrace their once-uncharted paths. And they’ve got the means to pay for it.

Retailing risk

Zegrahm Expeditions’ Scott Fitzsimmons understands this perfectly. In business since 1990, serving some 2,000 customers per year, with roughly $14 million in 1999 sales, his company has comfortably established itself as “a boutique travel company,” he says. Of his well-heeled clientele, he explains, “We’re constantly looking for new places . . . to find new frontiers. They’re definitely the most well-traveled [people] in the world. It’s really not a matter of money. The biggest challenge that we face is time. These are people who are high-achievers, and time is not on their side. I’d say they were time-impoverished.”

In a phenomenon similar to Everest-mania, Zegrahm is benefiting from another famous disaster narrative so familiar to the new leisure class: the Titanic. For $35,000, two clients and the pilot of a tiny sub descend two and a half miles to view the celebrated hulk. “This is a trophy. One hundred people have seen the Titanic wreck—that’s it,” enthuses Fitzsimmons.

Is it the romance of the tale that appeals to adventure travelers? “There’s absolutely no question. The whole Shackleton story is a great one. All of our passengers know it,” he declares, referring to Caroline Alexander’s best-selling The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition. Accordingly, Zegrahm and several other operators are expanding into Antarctica and South Georgia Island (where Shackleton famously completed his epic 1916 self-rescue mission after venturing 800 miles in a 22-foot boat). The price? About $10,000.

For tourists disembarking in these frozen climes, the jarring Zodiac rides only add to the appeal, says Fitzsimmons. (These fast rubber boats can flip or simply bounce passengers to injury.) “The things that people remember most are the unusual things that happen, the things off-brochure. This is what people seek out . . . something that wasn’t planned. A little bit of danger does sell.”

Down and up markets

Sales have also been good at Tropical Adventures, doubling in the past 10 years for the country’s oldest, largest packager of diving trips—incongruously located here in nontropical Seattle. “Divers who have been around for a while have all done the Caribbean,” says Linda Leszynski, “so they’re branching out.”

For those who crave added value on excursions in the $2,500 to $3,000 range, Leszynski explains, “We’re getting into the shark diving trips in South Africa. That’s pretty exciting. It’s cage diving, and you dive with the great whites. It’s total adrenaline.” (An underwater enthusiast herself, she adds that she also intends to make such a trip.)

Closer to home, Mt. Rainier produces no less adrenaline—and is more popular than ever. The 31-year-old guiding firm Rainier Mountaineering Inc. holds the concession to the most frequented route on a peak that has claimed 93 lives in its climbing history, but the line of customers could be much, much longer, according to RMI’s Joe Horiskey. “We’re limited in the numbers of the people we can take up,” he explains of national park restrictions that also cap RMI’s fees. (The standard three-day school/summit bid costs about $700.) “There is tremendous demand” from clients, he continues, but park quotas have restricted RMI’s numbers to about 3,000 attempts in the past several seasons (up from roughly 2,000 a decade ago), limiting the company’s gross revenues to the $1.5 million to $2 million range. As for the recent spate of alpine disaster stories, “That kind of advertisement perks up our business,” Horiskey concedes. Was business hurt by the June 1998 avalanche that killed an RMI climber on the Disappointment Cleaver? “No,” he answers.

That assessment goes even further and higher. Mountain Madness expedition leader Scott Fischer perished in the Everest ’96 storm only two months after Seattle Weekly‘s Bruce Barcott had asked why he conducted such dangerous trips. “Business,” he replied. “This is something I’m good at; it’s what I do. And there’s a demand for it.”

Keeping the customers satisfied

Those demands increase with the ability to purchase such adventure. According to the ATS, adventure travelers boast higher-than-average levels of education and income. And they expect a lot for their hard-earned money. “Why Bhutan?” an acquaintance of this writer was asked of a trek costing upwards of $4,000 to the tiny Himalayan kingdom that tightly controls the number of its visitors each year. “Because I can,” replied the smart, prosperous San Francisco consultant with evident self-satisfaction.

The attitude of such moneyed customers is becoming more prevalent, according to Scot Macbeth, now semiretired in Port Townsend after 30 years of guiding treks. “I’m glad I’m not in it anymore,” he says, “because you’ve gotta take clients on and off the pot and they expect all kinds of stuff.” As the Himalayan trekking business began in the late ’60s, he recalls, “I dealt with Sierra Club types and mountain people. If they took a misstep and broke their foot, they’d go home and put a Band-Aid on it. And here you get sued now. The liability is just enormous.”

“People will come saying they’ve been to a climbing school, and then you’ve got to train them all over again,” he continues. Does this r鳵m頩nflation bespeak an excessive sense of customer entitlement? “Oh, sure! A lot of them are there not because they love the mountains. They’re there because it’s fashionable, and they want to come back and say they’ve been to Everest. There’s not as many people going [today] that really love the hills. They’re going for cocktail conversation to be able to say they’ve been there.”

Thus the adventure travel distinction between “hard” and “soft” trips begins to blur, which is not such a bad thing for aging baby boomer clients—one of whom will turn 50 every eight seconds for the next 15 years (a statistic widely quoted within the industry). In other words, the peaks may get lower, the walks shorter, the beds cushier, and the meals larger, but the “adventure” moniker will profitably remain and gain prominence within the travel biz. (Can a Disney World adventure travel ride be far behind?)

Final sale

However, even soft trips have a way of turning hard. Noting that her company pulled out of Uganda a few years before the March ’99 kidnapping and murder of an Oregon couple and six other ecotourists, REI’s Dunbar says, “We as a business are probably more cautious than other companies.” Does that cost them the patronage of more adventure-minded clients? “I’m sure it does,” she says unconcernedly, knowing that it’s live, repeat customers who count.

Inevitably, however, more accidents will befall the most extreme alpinists, sailors, and explorers, and new best-sellers will be written about their mishaps. From this burgeoning literature of disaster nar- ratives, more slick adventure travel brochures will be mailed, more itineraries planned, and more tickets sold. As with the Titanic, Everest storm, and Shackleton’s flight from his ice-crushed ship, this underlying, morbid rubbernecker element contributes to the romance of such travel—even if we’re supposedly taking vacations to get away from the routine commuter smash-ups along I-5.

Then—if the travel company does its job properly—we go back home exhilarated but alive to start planning our next trip. No matter what we think we’re buying, Macbeth chuckles, “The purpose of an adventure travel guide is to make sure the clients don’t have an adventure.”

Lights, camera, adventure

Why travel when we can watch her on TV?

PIRELLI HAS its pinups, and the adventure travel biz has its Holly Morris, the photogenic 35-year-old Seattle editor turned globe-trotting adventure diva. Having forsaken her old gig at Seal Press, she’s rapidly become a very public face for the burgeoning women-oriented adventure travel sector. This year, her privately backed local company produced an hour-long Adventure Divas pilot on Cuba (seen on KCTS), with six more episodes on order. Her Web site, www.adventuredivas.com, promotes the show, charts her activities, runs a few articles, peddles some merchandise, and encourages postings and feedback from fellow reader-travelers. Additionally, Morris is serving as a host for the Discovery Channel’s Treks in a Wild World series, from whose recent assignment in Niger she had just returned when we caught up with her.

At first glance, it might seem that Morris is simply capitalizing on the current rage for extreme travel and disaster stories, trying to elbow her way into an already crowded market. “I think people are still eating that stuff up,” she concedes. “But I do think there’s a real yearning for travel with meaning. I think that adventure is as much or more a philosophical notion, more a way of living one’s life—whether it’s at home or on the road—than it is about scaling any mountain.”

So she won’t be bungee jumping or solo trekking across the Gobi Desert in a quest for ratings? “We’re definitely not going there,” she laughs, speaking of the need to emphasize faces over places, culture over danger. “So few of the travel or adventure programs that you see address that. I really believe that you can have an idea-driven program and it will have commercial viability.”

Indeed, Morris speaks of wanting to cultivate a sense of inner adventure, unlike the Into Thin Air-inspired notions of stereotypically male, hard category adventure travel. “That internal revolution is a big part of travel, especially, I think, in some ways for women,” she notes, adding with a chuckle, “I know this sounds kind of Oprah.”

“This thing grew from a fairly philosophical basis in that we really wanted to profile women around the world and explore countries through the eyes of a handful of women,” Morris continues. “In some ways, our name is a bit misleading. It is about taking risks sometimes, and it is about facing fear. But we wanted a people-driven pilgrimage.”

Seeking to get that philosophy across, she acknowledges that selling her own image has become part of her company’s marketing plan. “Personally that’s been a big shift for me. It meant I had to be a more public person, which has its ups and downs.”

Morris also notes the irony that before, as an editor, “I found myself behind a desk living vicariously” through the adventure travel press, and now we’re the ones living vicariously through her. If she makes a buck, fine, but this diva also hopes to see “regular people being inspired to their own potential”—after first watching her show, of course.

B.R.M.