AFTER EVERY ELECTION, pundits and analysts seek to distill the “message” from the voters. This year, the voters’ message came in loud and clear:

We can’t make up our minds.

The Democratic and Republican faithful spent Tuesday night milling around well-appointed hotel ballrooms as the night’s two marquee races—Gore/Bush and Gorton/Cantwell—remained too close to call.

Elsewhere, voters were cutting their taxes (by approving state Initiative 722), raising their taxes (by supporting Seattle’s massive parks funding package), defeating efforts to rewrite the state budget (through the failure of road-building state Initiative 745), and supporting efforts to rewrite the state budget (through the victory of initiatives increasing school funding and granting automatic salary increases to teachers).

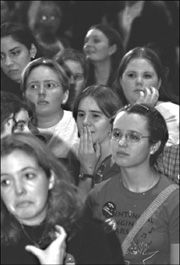

Supporters of former US Rep. Maria Cantwell crowded the Grand Ballroom of downtown Seattle’s Westin Hotel after local television stations declared her the winner in her race against ancient US Senate incumbent Slade Gorton. But their candidate delayed her triumphant entrance for more than an hour as results trickled in and her 20,000 vote margin grew slightly. Then, moments before Cantwell’s arrival, the crowd was shocked to learn that Republican George W. Bush had been projected as the winner of the presidential election over Democrat Al Gore.

Cantwell, arriving with arms wrapped around Democratic US Senator Patty Murray, stubbornly refused to declare herself the winner, even as chants of “No More Slade!” rocked the room. As Cantwell departed to cheers, Gorton could be heard on a nearby television as he assured Republican voters that his challenger’s lead wouldn’t last. (At last report, Gorton had retaken the lead.)

Fortunately, there are still a few things the ever-fickle electorate can count on:

- Tim Eyman will be back. The state’s initiative king suffered his first defeat with the failure of I-745, which would have forced state budget-writers to devote 90 percent of transportation funds to road building and repair. But, election night found Eyman looking on the bright side with the success of his I-722, a property tax limitation measure. “The only way you ever get tax relief is if you ask for it—and tonight the voters asked for it.” Eyman pledged to defend I-722 against the inevitable court challenge and to return next year with another initiative forcing a public vote on all tax increases.

- Tim Eyman’s critics will be back, too. Aaron Ostrom, the Seattle environmental leader who chaired the No on I-745 campaign, says voters weren’t fooled the initiative-pusher’s simplistic solutions. “They recognize that a roads-only approach is a recipe for more pollution and more traffic,” he said.

- Seattle residents will spurn trends by continuing to raise their own taxes. A parks funding plan—the largest tax levy in city history—received 56 percent voter support. An elated Mayor Paul Schell promised that the voters will get value for their investment. “The citizens are really stepping up and responding to the future,” he said. “Now we’ve got to make sure we give them their money’s worth.”

- People will continue talking about the monorail. More than 57 percent of city voters backed a $6 million feasibility study of an elevated transit system within city limits. Interviewed at the initiative’s surprisingly dull victory party, author Peter Sherwin insisted that the monorail isn’t intended to replace the planned regional light rail transit system. Yet Sherwin also ripped Sound Transit for failing to adequately consider monorail technology in the first place—implying that the monorail initiative succeeded because his proposed system was superior to light rail.

- King County residents like taking the bus. A sales tax hike to boost bus service got 53 percent of the vote and the county’s huge “no” vote on anti-transit I-745 helped put that initiative into the statewide loss column.

WHETHER THE fledgling Green Party has any future after this year’s election is questionable. Presidential candidate Ralph Nader had set a goal of 5 percent of the national vote, which would have qualified the party for presidential matching funds in the 2004 election. But many potential Green voters were concerned about aiding a Bush win and sought to swap their votes with residents of states in which either Bush or Gore was considered to have an insurmountable lead.

Neither plan worked. Nader barely drew 3 percent of the national popular vote, yet managed to play the spoiler in some states narrowly split between the candidates of the two major parties.

But, if the Democrats expected contrition, they would have been sorely disappointed by the Green Party’s Tuesday night gathering at the Speakeasy Caf鮍

A defiant Rev. Robert Jeffrey exhorted Green Party backers to hold their heads high, and not apologize for following their consciences in the presidential campaign. Jeffrey had little sympathy for the Democrats. “The very fact that [the Democrats] had to beg for the Green Party vote shows that we were right in the first place,” he intoned. “Gore is not more important than the future of the planet.”

Jeffrey and other Green Party supporters excoriated the Gore campaign for pressuring Nader supporters to switch their votes to the “lesser evil” among the major party candidates.

The Democrats’ tactics may have worked here; Nader’s numbers were unimpressive as Gore coasted to a relatively comfortable victory in Washington state. But Nader’s campaign, and the energy it attracted from disaffected, primarily young activists, was symptomatic of Gore’s failure to excite his progressive political base.

More encouraging for Seattle’s Greens was the finish of NOVA School teacher Joe Szwaja, who pulled about 20 percent against incumbent Seattle congressman Jim McDermott. This was reportedly the highest percentage ever tallied by a Green Party candidate in a US Congressional race. It came despite a tiny campaign treasury and limited local media coverage.

Now that he has a bit of name recognition—even as just that guy with the funny name—will Szwaja run again, against McDermott or for other local offices? “I really think that I may,” he said. “The Greens are very, very new. We set out to build a real alternative. I want to be part of that.”

Yet the conundrum that plagues the Greens—are they an independent party or a Democratic interest group?—was still in evidence on election night. The crowded room erupted in euphoric cheers at a premature announcement that Cantwell had beaten Gorton. Similarly, gloom followed the announcement of a possible Bush victory—even though Nader had repeatedly insisted that both major party candidates were equally unpalatable.

As the night went on, one tally showed Bush and Gore’s national totals less than 300 votes apart. Washington state can’t boast of quite that equal a split, but the divisions between urban Puget Sound and rural Eastern Washington, between legislative leadership and initiative-based voter mandates, and between Democrats and Republicans, have seldom been more evident.