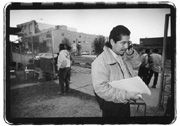

IN PREDAWN DARKNESS, 25 Latino men begin their daily quest for work in Belltown. Smoking and talking in an odd triangular lot beneath the Aurora overpass at the corner of Western Avenue and Battery Street, they are waiting for the hour to strike 6, when a year-old job placement center for Latino day laborers will open its gate. Run by the nonprofit Casa Latina, the facility is a makeshift affair. Its only structures are a small trailer and a wooden shelter draped with blue tarp for walls, spruced up by a few surrounding plantings and two freestanding, colorful murals.

Casa Latina does have, however, a set routine. At 6 am sharp, the gate opens and the men line up to get into the trailer, where a staffer writes down names, gives everyone half a blue raffle ticket, and puts the other half in a canister. The men then take turns picking half-tickets from the canister—a serious business since it determines who gets the first shot at that day’s jobs. There’s typically still a while to wait before employers call in or show up in person, so many walk down the street for a free breakfast at the Millionair Club, the city’s veteran organization for helping day workers.

The Millionair Club gives food to all comers but, unlike Casa Latina, requires identification documents for job placement that many Latino immigrants don’t have. After a breakfast of meat sauce over bread with milk, the workers return to the Casa Latina site for more waiting and, for those who choose, a daily 7am English class that focuses on practical language.

As half a dozen laborers on chairs beneath the wooden shelter repeat “cent-i-meters,” a nearby worker in a red jacket and jeans indicates he is eager to say something. “These guys right here, they’re trying to find protection,” explains Carlos, a 31-year-old Mexican immigrant. “That’s the whole point.”

Before this site opened, many of these men worked the longstanding labor market of Belltown’s streets, hopping into cars and pickups that cruise the neighborhood for workers. Risks abounded: Employers didn’t always pay after the end of a grueling day, there was no compensation for on-the-job accidents, and even climbing on board a truck could be hazardous to one’s health due to the sometimes literally cutthroat competition between workers. Casa Latina tries to counter those risks by organizing workers, helping to establish guidelines such as a wage scale from $9 to $12 an hour, and providing lawyers to pursue claims for workers’ compensation and unpaid back pay.

Not all day laborers have appreciated the effort. As a matter of fact, some have slashed the tires of Casa Latina staffers and made death threats against people at the site. Correspondingly, some people in the neighborhood believe the project has had mixed success. This belief has fed a debate over a new expansion plan by Casa Latina, a controversy that says a lot about how much Belltown has changed in a remarkably few short years.

LAST SUMMER, Casa Latina built its day workers’ center as a temporary trial facility. Now, the organization has teamed up with the respected nonprofit Plymouth Housing to plan a permanent building on the site that would continue its current function and add 40 to 50 units of low-income housing, targeted in part at Casa Latina’s largely homeless clientele.

On the surface, the debate over the expansion plan has revolved around its effect on prime Belltown concerns these days— the lack of views and open space in a neighborhood that has become the city’s hippest and turned almost every patch of land into a high-rise. The Casa Latina site avoided development largely because of its peculiar shape and because it is owned by a public entity: City Light.

Even when Casa Latina began renting the land last year, the space continued to feel undeveloped because of its small-scale structures. As you walk along First Avenue, past the sleek cafes and condos that dominate the neighborhood, a striking opening arises above the site, offering a view of Puget Sound and the Olympics. Some kind of change is in the cards, however, with or without Casa Latina. City Light intends to surplus the land when the organization’s lease runs out at the end of the year.

“That is the last view corridor left in Belltown,” says Gretchen Apgar, owner of the Speakeasy and president of the Denny Hill Association, Belltown’s broadest neighborhood group. She wrote a letter in May urging the city parks department to create a park at the site, noting that the recent Belltown Neighborhood Plan, as well as several previous neighborhood plans, envisioned open space on Western. She received a letter last month indicating that isn’t likely to happen. Now, Apgar just hopes that Casa Latina will preserve as much of the view as possible. Although Plymouth Housing has estimated it needs four or five stories to make the project economically feasible, some innovative ideas were proposed at a recent design workshop. One suggestion, for example, was a window that would allow you to see through the building from First Avenue.

Apgar seems amenable. Like a number of community leaders, she wants to work out a solution with Casa Latina because of the important work it does. She calls the Latino day workers who have hustled the neighborhood’s streets for as long as she can remember “almost like a symbol of Belltown.” But that’s the old Belltown, of course; the seedy, eclectic Belltown that was a natural haven for the down-and-out.

That the neighborhood has radically changed underscores, to some, the need for a project such as Casa Latina’s. “There’s been a lot of displacement in Belltown,” says Zander Batchelder, president of the Belltown Community Council. “We need to make up for some of the housing that was lost when the high-rises went up.” Batchelder acknowledges, though, that not everyone in the neighborhood feels the same. The Belltown Business Association, in particular, has been a vocal critic of Casa Latina’s expansion plan. At the recent design workshop, BBA presented a letter to Casa Latina arguing for a park.

DEVELOPER PETER ERICKSON, whose just-finished condo complex sits across the street from Casa Latina’s day workers’ center, helped formulate the business association’s position. Erickson exemplifies the new Belltown in many ways. His condos, called Belltown Lofts, cater to a creative high-tech crowd with industrial materials, cavernous spaces, and state-of-the-art wiring. Rooftop patios afford not only a stunning view of the Sound and the Olympics, but of the Microsoft-owned Visio Corporation. RealNetworks is a short walk away.

It would not be fair to cast Erickson as a ruthless gentrifier. Prices in his development run as steep as $860,000, but he has also taken pains to keep some units as inexpensive as $150,000; plans to subsidize a couple of units for artists; and has built his complex around an outdoor courtyard, European style, to foster a sense of community. It would be fair to say, though, that Erickson disapproves of aspects of the old Belltown, specifically the occasionally antisocial behavior of its ragtag labor force. “They’ll be taking a piss” in public, he says. “They’ll be taking a crap under the bridge.” Some, to be sure, also drink, do drugs, and harass passing women.

In criticizing Casa Latina’s newest plan, Erickson eschews the social issues and emphasizes the importance of open space and view. Looking down on the day workers’ center from one of his condos, the lanky developer with longish hair and glasses broods, “If you build that site up, you’ll lose a place for the mind to expand.” But coming from him, the argument is a little ironic. He is, after all, arguing against the loss of open space from the perch of his own development. Although he seems sincere, his problems with Casa Latina go deeper.

The history of the day workers’ center tells the tale. Surprisingly enough, the center began with the enthusiastic support of local businesses. A couple of years ago, businesses working on a street improvement project were trying to figure out how to deal with sidewalk laborers, whom they considered a detriment to sales. When Casa Latina moved its offices into the neighborhood, the nonprofit, which was teaching English to Latino laborers, seemed like a resource businesses could use. The parties began to talk.

Casa Latina didn’t see the presence of workers on the street as a problem per se. “It shouldn’t be a crime to be looking for work,” says the organization’s executive director Hilary Stern, adding that drunken harassers make up a small percentage of the population. Casa Latina was interested, however, in helping the street laborers find a more “dignified” and safer way of looking for work, according to Stern.

Together, Casa Latina and local businesses hit upon the idea of a center that would gather workers together at one site and take them off the street. Businesspeople, including Erickson, chipped in thousands of dollars apiece and successfully helped the nonprofit lobby the city for funding and a location.

It was an unusual neighborhood success story. “You have to understand that everyone wanted this problem [the street workers] to disappear,” Erickson says. Yet, he emphasizes, businesses ended up changing their point of view entirely: Not only did they accept the inevitability of the workers’ presence, but they even donated money for Casa Latina’s center on Western.

Businesspeople thought they were donating money, however, to a facility that was only temporary, as spelled out in a carefully worded collaboration agreement between Casa Latina and the Belltown Business Association. The agreement stated that the facility would later be relocated to a permanent location.

Casa Latina’s Stern says, “Some people thought that having a temporary site would be the first step in moving the day workers out of the neighborhood. If they could organize a center, they could then move it some place else.” Stern didn’t necessarily agree, but was happy to go along with a temporary solution. Her harmonious accord with businesses started to unravel last spring when she told Mayor Paul Schell about new plans to develop a permanent facility at the very same site.

Having heard nothing about it beforehand, the businesses that had supported the center felt betrayed. “[Casa Latina] basically lost the trust of property owners, business owners, stores, restaurants, everybody,” Erickson says.

More importantly, businesspeople like Erickson have been confounded by an unexpected phenomenon. Despite the formation of the Casa Latina center, day laborers continue to work the street—not as many as before, certainly, but enough to make some skeptical of Casa Latina’s newest plan. “We need to solve the problem before we spend any more money on this thing,” says Belltown realtor Tom Graff.

Even Millionair Club executive director Mel Jackson, who helped get the Casa Latina center off the ground, has reservations about its operation. Jackson, who happens to be the current president of the Belltown Business Association but says he is voicing his own opinion as well, asserts that Casa Latina needs more staff to shoo away the men looking for work on the street. He points to the Millionair Club’s use of a security guard, who “as a motivational tool” will suggest that those hanging around move on to a library or park.

If Jackson’s disapproval of the street laborers seems surprising given his position, he makes a distinction between what happens in a center like his, where work is dispensed in an orderly fashion, and what happens on the street. Leaning his large frame over a cafeteria-style table at the Millionair Club, he stresses, “As a human being, and as an African American male, I can tell you there is nothing that excites me about seeing bunches of men running after a truck, trying to jump on before it takes off.”

THE LABOR MARKET of the street certainly is a strange scene. One sunny morning, only a few paces from the Casa Latina site on Western, a gray Dodge Caravan with an old woman driver and a younger thick-necked man in the front passenger seat pulls up beside a half dozen Latino men. The men swarm in and one is chosen in less than a minute, surely not long enough for much information to be exchanged about the job on offer. The chosen man is clearly pleased regardless. Hopping into the van, he eagerly leans forward to shake hands with the thick-necked guy, who reciprocates perfunctorily and nods curtly as the old lady leans on the pedal.

The exchange can’t help but call to mind the oldest profession of the street, prostitution. There’s the cruising car, the examination of anonymous talent, and the instant formation of a relationship not necessarily characterized by mutual respect.

What is degrading to one man, however, is liberating to another. “We feel much freer here,” says Martino, one of a couple dozen men lining Bell Street between First and Western that morning. Asked why he doesn’t use the Casa Latina center, he explains that he likes being able to choose his own bosses and believes he can negotiate a higher wage for himself. “We don’t like to be [bound] by rules,” he says. That’s the reason he says he became a day laborer in the first place, having once held down a steady manufacturing job in Texas.

So Casa Latina’s attempt to bring order and rules to this labor market was viewed by some as a threat, particularly when staffers began flagging down the cruising cars of employers and telling them to use its center. Casa Latina stopped that practice after men started coming by the center saying things like, “I’m going to kill you,” and two staffers came out of the center one day to find their tires slashed.

CASA LATINA’S Hilary Stern is far from defeated. She concedes that her organization may never be able to attract some of the streets’ free spirits. She contends, however, that many more workers are using the center than are working the streets. In the year it has been open, the center has placed 1,500 people in 5,700 jobs, including 150 permanent, full-time positions. And that’s without the resources to keep the center open all day (it closes at noon), without a real building, without even a permanent phone line to take calls from employers. (US West won’t install one without a building to put it in, so staffers use cell phones.) “If we could get a building and a regular phone line, we could handle a lot more business,” Stern says.

Business was indeed slow one recent morning, at least for the first two hours after the center opens at 6. And so as the men wait, getting coffee from an old drip machine in the trailer, they are happy to talk. They reveal themselves to be a varied lot. Some speak English perfectly, some not at all. Some have chosen this lifestyle, some yearn for something better.

The 31-year-old Carlos, who earlier explained the center’s function in protecting workers, tells me that he used to have a problem with alcohol. At one point, a truck ran over his leg as he was sleeping drunkenly in an alleyway. He came to Seattle from Yakima only a few days ago “looking for another way, a different life.” Sleeping in a mission shelter now, he hopes to save up money for an apartment.

Martin, a clean-cut looking young man wearing a purple T-shirt neatly tucked into green khakis, says he worked in a clothing store in Phoenix before moving here two years ago. He found retail didn’t pay much, about $7.50 an hour. Making $9 or $10 an hour through the center, he is able to send as much as $300 home to Mexico in a single week, apparently spending almost nothing on himself.

One of the oldest men is Alphonso, a 50-year-old in a McDonald’s cap. Alphonso also sends money to Mexico, where his wife and three children live. Through a translator, he says he can’t communicate well enough in English to do any other kind of work.

As the hours pass and 8 o’clock approaches, the atmosphere becomes more frantic. Cell phones start buzzing and trucks begin arriving. Jose, a worker who has taken on a leadership position, calls out four names. There’s a job moving furniture in a downtown office building. Four more names ring out—another moving job. An apartment building on Queen Anne calls. It wants two landscapers for $8 an hour, two dollars an hour less than the wage scale specifies. Jose puts it to the workers next on the list. Will they take it? They will.

Suddenly, a commotion ensues on the street. A white truck has pulled up next to the center and workers have surrounded it without waiting for management to negotiate the transaction. It’s hard to tell if the workers are from the center or from the street, but one is in the process of jumping in when Jose rushes in to stop him. He installs Carlos in the truck instead. Carlos is the former alcoholic who talked about the need for protection, and at least for today he has found some.