We Wear the Mask

by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1895)

We wear the mask that grins and lies

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask.

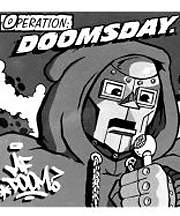

MF Doom steps to the stage bedecked almost exactly like the animated figure on his album cover—green hoodie and gray metallic mask. During his hour-long set, he never once removes the mask, rapping through a square cutout at its bottom. It’s odd to see someone rap without actually seeing them rap, particularly with Doom, whose rhymes drip with emotional honesty and are as much in the eyes as the mouth. The mask, he says, puts him in character. Yet Doom’s rhymes are clearly his own. The mask, it seems, is an obfuscatory tool, keeping the people in the audience from seeing into those uncomfortable spaces, granting access only on his own terms.

Years ago, MF Doom was Zev Love X, from the Native Tongue heirs apparent KMD. He and his brother Subroc meshed youthful exuberance and innocence with a scathing race-based sense of irony. Perhaps too young to fix the world’s problems, they still managed to create music that sparked critical thought as well as dance-floor movement. Their first album, Mr. Hood, put that ideology into action via a strain of spoken skits with the fictional title character, a synthesized white presence whose encounters with black youth left him puzzled.

Their follow-up, Black Bastards, was a bit darker, swapping some of the humor of Mr. Hood for a more aggressive aesthetic, lacing their sampled jazz-horn riffs with snippets from Last Poet Gylain Kain. But before the group could even release the album, Subroc was killed in a car accident. “At the time, I was on the boardwalk. I remember exactly where I was when I felt it, I could feel it, know what I mean? Automatically, I went to go call my moms and shit, ask her what’s up. That’s when, you know, she told me she had gotten a call from the police, that he was at the hospital or some shit. He had gotten hit by a car, and then later on that night was when he passed.”

To add insult to tragedy, Elektra soon dropped KMD without releasing Black Bastards, claiming that its Sambo-in-a-noose cover art was too controversial. (Fortunately, the album has since been released on Metal Face/Readyrock.) It would be years before Zev would reemerge as MF Doom, and his pain was apparent from his earliest singles, released on New York radio jock Bobbito Garcia’s Fondle ‘Em imprint. Doom’s first album as a soloist, Operation: Doomsday, was released late last year.

Even when death wasn’t specifically alluded to, it still dominated the music by Doom’s choice of backdrops, largely his use of quiet- storm R&B. Operation: Doomsday is that strange thing in rap—a sad record, one that makes no pretensions about wealth or fame and instead revels in a sort of emotional audacity. This is my pain. Taste it.

“Doomsday” is one of the album’s sprightlier tracks, linked together by tubular bells, though on the chorus Doom shrugs off the joy: “On Doomsday/ever since the womb/’til I’m back where my brother went/that’s what my tomb’ll say/ right above my government/Dumile/ either unmarked or engraved/hey, who’s to say?” On “?,” the clear tribute track, Doom laments, “These hoes be asking me if I’m you/ like my twin brother we did everything together/truly the illest dynamic duo on the whole block/I keep the flick of you with the machete sword in your hand/everything is going according to plan, man.”

What does it take for someone to rap behind a mask? Hip-hop is a genre that perhaps more than any other prizes authenticity, the ability to associate an artist directly with his lyrics. Wearing the mask opens a whole host of possibilities. One is reminded of Ghostface Killah during the Wu-Tang Clan’s early days, when he wouldn’t take photos without his face being fully obscured. Of course, it was assumed there were legal difficulties the man was trying to avoid by doing so.

Yet of all the Wu, it’s Ghost who wears his pain most plainly. The mask may well have had emotional resonance for him as well. On Doomsday’s closing track, Doom lifts a line from Zorro in Wild Style: “I’m not gonna finish my piece man, not with this lady around.” It might be a jab at an old flame (he fessed to a couple of others on the album), but it’s more a plea for privacy. This is my pain. Let me live it.