I MAY BE SLOW on the uptake, but midway through Gladiator, the blockbuster charged with reviving the sword-and-sandal spectacular, I finally realized it was basically a reworking of Ben-Hur. More accurately, it was a reworking of only one dimension of a film so epic that it consumes Gladiator whole and still has time enough to catalog a love story, a plague, and the birth of Christianity—all without a CGI crutch.

WIDESCREEN EPICS

runs June 30-July 6 at Egyptian

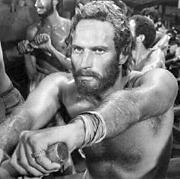

Naturally, Ben-Hur is the jewel of this CinemaScope epic series, which also features Dr. Zhivago, The Great Escape, Solaris, and The Thin Red Line. Each evinces great artistry, but it’s Ben-Hur, above all, that best uses the 2.35:1 aspect ratio in service of its sweeping plot. Its tale of the Judean prince whose personal conflicts reflect his tumultuous era simply refuses to be diminished by William Wyler’s massive sets and majestic set pieces: namely, the sinking of the Macedonian fleet and Chuck Heston’s famed chariot race—still one of the most exciting sequences in cinema history.

Conversely, Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 Solaris is a much more uncomfortable fit. It’s an interior meditation on love and regret that’s long on mood, short on spectacle. Confined to a desolate space station inhabited by three cosmonauts, Tarkovsky’s camera has nowhere to go except in lazy circles and slow, hypnotic pans down curved corridors. Unintentionally echoing Godard’s aphorism in Contempt that CinemaScope “wasn’t meant for human beings . . . just for snakes and funerals,” Tarkovsky proves that a 165-minute exploration of our dark consciousness begs a precision not suitable to the epic scale.

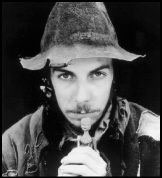

Neither Zhivago nor Great Escape suffers such an excess of subtlety; both are postcard views of war, seductive examples of old-style craftsmanship in the service of romantic vision. Despite David Lean’s lingering images—the cavalry charge, the dacha turned ice castle, branches tapping against a frosted window framing a child’s face—Zhivago is more about Julie Christie than Russian history. Likewise, John Sturges’ factually inspired Nazi POW camp is played for country-club laughs. (Still, who needs facts with Steve McQueen bustin’ out on his motorcycle?)

Near perfect in its mix of grandeur and complexity is another WWII epic, Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line. Malick asks suitably big questions, then dissolves the boundary between realism and mysticism to get the answers. By rendering his cast nearly unidentifiable and committing firmly to war’s chaos, he focuses on emotional truth with a somnolent dreaminess and painterly palette. Whether the camera is craning above swaying reeds or crouched low to observe a dying bird struggling along the ground, he conveys the true breadth and scope of Nature and our inextricable relation to it.