THE NUMBER ONE problem with the way non-hip-hop people relate to hip-hop is that they take shit way too literally. Hip-hop is a culture woven together from complex strands of symbolism; to understand hip-hop one must understand its elements. I’m not talking about musical or economic or social influences here. I’m talking about little self-contained worlds of meaning that artists manipulate through the spoken word into relationships that they’ve never had before, so that they pull and stretch and distort each other into new shapes and combinations. I’m talking about double-dutch nationalism and Moorish Science kung fu movies. I’m talking about the cultural logic of late capitalism. And—just to narrow it down—I’m talking about why it would be very difficult to understand modern hip-hop music if you didn’t have a comic book collection as a kid.

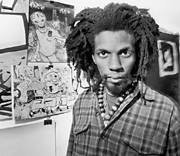

The most obvious influence of comics on hip-hop is seen in the brash colors and vivid characters of graffiti. As Seattle graffiti artist Specs points out, early writers pulled so directly from comics that you could actually pick out specific references. “In the stuff I was seeing from New York, you could see what comics they read,” he recalls. “‘Cause a lot of that stuff was looking like Jack Kirby-influenced, and later like some George Perez-type stuff. Then, later, it was Vaughn Bode.”

But it certainly doesn’t stop there. Comic imagery can be found throughout hip-hop culture, from the names of DJs and groups to the attitude of b-boys and b-girls. Not to mention the lyrics: Hip-hop’s first hit, “Rapper’s Delight,” had Big Bank Hank actually stealing Lois Lane from Superman (although the credit really should go to Grandmaster Caz, who wrote the lyric). Comics crept into every aspect of hip-hop, and if you think about it, it’s not surprising. The message of most comics is that mild-mannered working people, such as the Daily Planet‘s Clark Kent (not to be confused with DJ Clark Kent), are secretly much more powerful than anyone could imagine.

It’s not hard to see how this would resonate with working-class urbanites, especially as they watched the Black Power Movement disintegrating in the late ’70s, an era defined more by individual growth than collective organizing. In a sense, comics were one of the period’s most subtle self-movements, because their effects are only now being felt. Moreover, during the 1970s—when most of today’s hip-hop artists were kids—mainstream comics began to rely on complex characters, Byzantine plotlines, and unusual philosophical propositions. I, for one, never really understood the relationship between Superman, Bizarro Superman (who was like the anti-Superman), and Superman of Earth 2 (who I guess was the same as Superman, but in another dimension or something). And you’re talking to a guy who reads Frankfurt School critical theory for fun! Comics in the ’70s were art, literature, and junior high school motivational assemblies all rolled into one.

EACH OF THESE aspects was important to Specs, who is also an MC and producer. “The first way it influenced me was mostly the art,” he says. “But then, also, some of the philosophy that was going on in some of the comics . . . made for an embodiment of inner strength of some sort. It always helped me, as a kid, feel confident.” Then, as now, the idea of confidence as hidden power links comics with hip-hop.

For Kylea, MC for Beyond Reality, this confidence allows hip-hop artists—like superheroes—to present maximum excitement with minimum risk. Is a superhero, she asks, “gonna get crushed by this building? You know they’re not gonna get crushed! They might go through something, but they’re still gonna come out. So we know that being in this music, we may go through some obstacles, but we’re still gonna come through. You know what I’m saying? You might get a building or two that try to fall on you, but you just gotta push it off. Because you’re the one that’s creating the story.” Hip-hop MCs are not just superheroes, they’re actually metaheroes. Their superpower is the ability to create themselves (and the world they move through). Needless to say, this ability can bring great freedom when it comes time for personal expression.

“You can separate yourself from your art, in a way,” explains local artist Michael Hall, Specs’ alter ego. “‘Cause you can take the character that you’ve chosen to embody and then make him represent all these different types of things. You can say things maybe you wouldn’t normally say. Be a little bit more out there than you normally are. You can be extreme in so many ways, just by having that other personality.”

“With me, the alter ego is like a spirit,” says Kylea. “I open up myself to allow that energy in, and then I get to sit back and watch. And when I freestyle—that’s my alter ego.” Through improvisational rhyming, she speaks herself into existence.

A familiarity with comics can affect expression in other ways, too. As University of Virginia hip-hop professor Dr. Kyra Gaunt points out, neither comic books nor hip-hop songs can afford to waste words. “The span of the narrative is very compact,” she says. “Everything is very streamlined. You have to put your spin on things, and put your style on things, very quickly.”

Like comics, hip-hop has developed a broad range of techniques for quick, yet thorough, storytelling. For example, it is easy to imagine the Geto Boys’ “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” in comic form: “I make big money/I drive big cars/everybody know me, it’s like I’m a movie star/but late at night/something ain’t right/I feel I’m being tailed by the same sucka’s headlights.” Picture this lyric in a thought bubble above the head of a character looking in his rear-view mirror. In less than 35 words, we get an entire pathology of competing impulses and paranoid imagery.

The idea of the MC as a recurring character moving through different situations in his or her songs also has its roots in comics. As Kylea points out, most superheroes “had like a series. So that’s almost like the same thing with a song. Each song could be similar to another issue of a comic book. You look to read that next comic book for the story to continue. You always wanna look forward to more, especially if you were feeling what you read, or feeling what you heard.”

FROM A STYLE of storytelling to a model of character development to a strategy for expressing power in a dangerous world, the comic universe inspired and even helped shape much of hip-hop’s worldview.

A local MC and I sometimes joke about teaching a class called “Hip-Hop for Parents.” The idea would be to guide adults in making an informed evaluation of what their kids listen to, as opposed to basing their assessment on media stereotypes. And the first lesson would almost certainly be this: If you want to understand what someone is saying, you have to understand where they’re coming from. Even if they’re coming from Krypton.