THIS WAS NOT SEATTLE.

Protesters against the World Bank and International Monetary Fund were foiled in their attempt to shut down the April 16-17 meetings of the two international financial institutions. But police only occasionally resorted to the types of violence and chemical warfare that characterized the futile Seattle police response to last fall’s WTO protests.

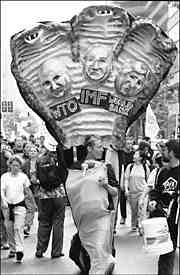

Yet the IMF/World Bank protests were successful even before they began, focusing rare attention on the destructive policies of a US-dominated international financial agenda. In 50 years, no organized US movement had questioned the neoliberal assumptions that have aided Western corporations and decimated indigenous economies throughout the Third World. While “IMF Riot” is its own term, referring to the civil disorder that frequently results when governments are forced by the IMF and other international lenders to open markets and slash public social spending, the American public has remained almost entirely indifferent.

That’s now changed. The next step for the movement spawned by Seattle’s anti-WTO protests, a movement partially supported by the protectionist instincts of labor, was to truly globalize it. The Mobilization for Global Justice, the umbrella group that sponsored the DC protests, vowed to bring to the capitol “the spirit of Seattle,” but this protest was different in important ways. The World Trade Organization can and has struck down American laws, but World Bank and IMF policies do not directly impact US citizens. And almost none of the some 10,000 protesters willing to risk arrest in downtown DC streets were from the DC area; one of the reasons subsequent protests on Monday, April 17, were relatively small and disorganized was that so many people had to catch a ride or take a flight home after the big day.

The police, too, were haunted by Seattle. While protesters did almost everything the same in hopes of repeating Seattle’s victory, DC police responded to the media hype with aggressive tactics. Several raids in the week before April 16 resulted in the seizure of hundreds of chains, lockboxes, and “sleeping dragons” (pipes that fit over linked arms to make it more difficult to separate them) intended for use in seizing and holding intersections. On the morning of Saturday, April 15, fire officials closed down the “convergence center” headquarters, a space for protesters from out of town to check in for meetings, trainings, and strategizing. (Police also somewhat ludicrously claimed to have seized the makings of a Molotov cocktail in that and other raids.) Demonstrators were largely undeterred by the harassment, falling back quickly on an alternative site at a community center in northwest DC. But the moves heightened fears that police would crack down on the Sunday, April 16, big event itself. To make matters worse, an International Action Center-sponsored, unpermitted march on the eve of the big event was funneled into opposing police lines, with the resulting arrest of some 600 marchers.

That turned out to be the major arrest of the whole weekend. By the previous Thursday, DC police had established a security perimeter around the IMF and World Bank, and when dawn broke on Sunday and thousands willing to risk arrest descended on the dozens of city blocks around the perimeter, they found that police were generally content to let them peacefully occupy intersections. (It helped that IMF/World Bank meetings were being held on a quiet Sunday morning, so protests weren’t snarling already brutal DC rush hour traffic.) At 6:30am, DC police chief Charles Ramsey stated that as long as protesters refrained from violence, police would let the demonstrators have the day. With demonstrators generally unfamiliar with the city’s geography, police had little trouble finding back entrances through protest lines and escorting delegates into the IMF/World Bank meetings. IMF spokesperson William Murray later conceded that some delegates were inconvenienced by the protests, but they were safely contained several blocks away from the meetings.

Chief Ramsey, who spent the day walking the streets and talking with officers and protesters alike, generally kept to his word about refraining from cracking down on the protesters; only about 40 were arrested on April 16-17. Chemical weapons were rarely deployed: once on Sunday, when an anarchist contingent rolled a large barrel toward police lines, and once during a police line confrontation on Monday. A few other confrontations flared at various intersections when protesters, usually without the numbers to clog the intersections, dove in the paths of oncoming police vehicles. No evidence supporting protest spokesperson Nadine Bloch’s claim that police used rubber bullets was found. While much was made ahead of time of anarchist groups that renounced the Mobilization’s nonviolence guidelines—and those were generally the groups that engaged in more violent confrontations with police—there were no broken windows, no looting, no fires, and only a little graffiti on the office buildings of downtown DC.

Unquestionably, DC police, with more personnel (some 1,400 officers were deployed with thousands more on standby), more favorable geography, better planning, and the benefit of hindsight, managed to avoid the pitfalls that cost Seattle Police Chief Norm Stamper his job. Seattle’s leadership had aspired to holding the meetings while allowing dissent. DC managed the balance.

For the largely youthful protest movement that has swelled up around issues of global capital, there are more questions. DC followed almost exactly the organizing model of Seattle. Demonstrations, teach-ins, and workshops took place the preceding week, a big permitted rally accompanied the street action, an Independent Media Center provided a million hits’ worth of live streaming and media content on its Web site, and a decentralized affinity-group structure divided the city into pie wedges and then used stationary groups and roving bands to try to cast a net over the neighborhood.

In Seattle, it all magically worked. In DC, with the burden of additional advance attention and expectations, a great deal was accomplished, but the officials meetings went undisrupted. Similar models will be used when multi-issue protests confront the Democratic and Republican national conventions in Los Angeles and Philadelphia this summer. But beyond the power of this type of protest to gather headlines, the question of how it will lead to different policies remains. How can thousands upon thousands—even millions—of outraged citizens deflect the juggernaut that is exploitative transnational capital? For all of the exuberance of the April 16 protests, that fundamental question is still unanswered.