“ONE OF MY BEST TRAITS is that I try to push things forward,” says techno DJ and producer Richie Hawtin. “I try to reinterpret things from the past, rather than just repeating them. That’s not always easy—the difficult thing is to find the balance between what is comprehendible and what is not.”

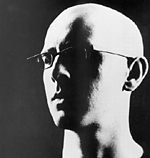

Richie Hawtin

Showbox, Thursday, February 17

Maintaining this balance is what Hawtin, who is touring in support of his new DJ-mix album, Decks, EFX & 909 (Novamute/M_nus), has dedicated much of his career to. Growing up in Windsor, Ontario, Hawtin became a fan of New Beat groups like Belgium’s Nitzer Ebb, early German electronic bands like Kraftwerk, and the pulsing electro hip-hop coming out of New York and LA. He soon discovered techno, which was in its developing stages mere miles away in Detroit. Hawtin became a DJ, styling himself after Jeff Mills, a Detroit radio jock who’d dubbed himself “The Wizard.”

Then he set his sights higher. Trying his hand at producing, Hawtin attempted to hawk his tracks to Derrick May, Detroit’s foremost DJ/producer and the founder of Transmat Records. May wasn’t interested, so Hawtin released them himself, starting +8 Records in 1990 with his friend and fellow Windsor DJ John Aquaviva.

The label’s output proved highly influential. Working under the names Cybersonik and F.U.S.E., Hawtin was pushing techno into harder, faster terrain, with his tracks’ velocity increasing the average tempo from about 130 beats per minute to 150. When the label’s European fans took the baton and began making the rougher, more head-drilling noise that came to be known as “gabber,” Hawtin moved sideways into slower but still intense acid-techno. Adopting the name Plastikman and creating an unforgettable cartoon logo to go with it, Hawtin released the notorious Sheet One in 1993. The CD’s cover was designed to look like a paper blotter of LSD, complete with perforations, and it appeared real enough that a Texas fan was arrested when the police discovered a copy of the album in the young man’s car.

Hawtin released Plastikman’s 1994 follow-up, Musik, then experienced delays while recording a third album, including his own run-in with the law. On the way to a gig in New York just after the bombing at the 1996 summer Olympics in Atlanta, Hawtin got stopped at the Canadian-US border; his shaved head, tiny glasses, intense demeanor, and obscure electronic equipment aroused suspicion.

He persevered, recording sporadically and organizing parties in Detroit. After a four-year wait, in 1998 he released Consumed, which winnowed Hawtin’s sound down to its barest essence. Full of bubbling, discreet tracks that were insinuatingly subtle even for the self-described “complex minimalist” who’d made them, they could fill a room or clear it. The album’s beats barely registered; where Hawtin’s Roland TB-303 bassline synthesizer had once generated throbbing, thrilling pulse-riffs, here it sounded like it had been strapped to a rock and was struggling, without much success, to free itself. It was, as critic Simon Reynolds wrote, “End-of-the-journey music.”

DECKS, EFX & 909, on the other hand, sounds like the party held after the journey’s completion. Hawtin layers his records atop one another, adding texture and space via the Roland TR-909 drum machine and a handful of effects processors. On their own, the clicking beats and vaporous feel of many of Decks‘ tracks are deliberately unfinished, which makes them as ideal for stacking and interlocking as Lego pieces. Hawtin connects them like a gamelan orchestra conductor, lining up single rhythms into an undulating whole, and it’s livelier and more physical than any of his music since the early +8 tracks.

“I thought it was the right time to do it, because it seemed like the next step forward,” Hawtin says of Decks. “It’s all about timing. If I’d done a record like Consumed eight years ago, it would have been hard for me and for other people to get their heads around it. I wanted to connect into something thicker and bigger, but to make something out of smaller parts.”

The new disc isn’t Hawtin’s first DJ mix; he also spun a Mixmag Live! disc for the British dance monthly and cohelmed the third volume of the X-Mix series, where he and Aquaviva spun tracks from the +8 catalogue. “Those were the beginning stages for what Decks, EFX & 909 would become,” Hawtin says, “because they were live with a little bit of added production here and there.” Another important influence was Live at the Liquid Room, Tokyo, Jeff Mills’ 1996 DJ mix, a brutal, passionate display of deck technique that sounds like the underground techno equivalent of the first Ramones album. “His mix CD was unlike any other,” Hawtin says. “It captured the spirit of Jeff Mills in a live sense. I wanted to do something that did the same thing for me—that captured the spirit of a Richie Hawtin DJ mix.”

On the road, Hawtin is sticking close to the Decks template. “Everything I’m doing lately is with the same equipment as I did the CD with,” he says. “It’s a setup that works really well for me.” As for what comes next, Hawtin promises something else altogether. “I’m working toward finding a completely new direction. It probably won’t be like Decks, EFX, but it will still be recognizably mine.”