Early on in this story of how he adopted a baby boy, Dan Savage and his live-in lover, Terry, walk into a conference room already occupied by six heterosexual couples and an

adoption counselor. All are in Portland to meet for the first time as part of their adoption agency’s two-day orientation session for prospective adoptive parents. (Savage declines to name the agency, although it is easily recognizable to anyone familiar with current adoption practices.) Savage is more or less proactively hostile, assuming—among other things—that some of the families in the room are fundamentalist Christian, and therefore gay-bashers. His first thought upon seeing the group is, “They hate us.” And as the meeting gets under way, he writes, “Terry and I began to feel more out of place, and even more conspicuous than we had when we first walked through the door.”

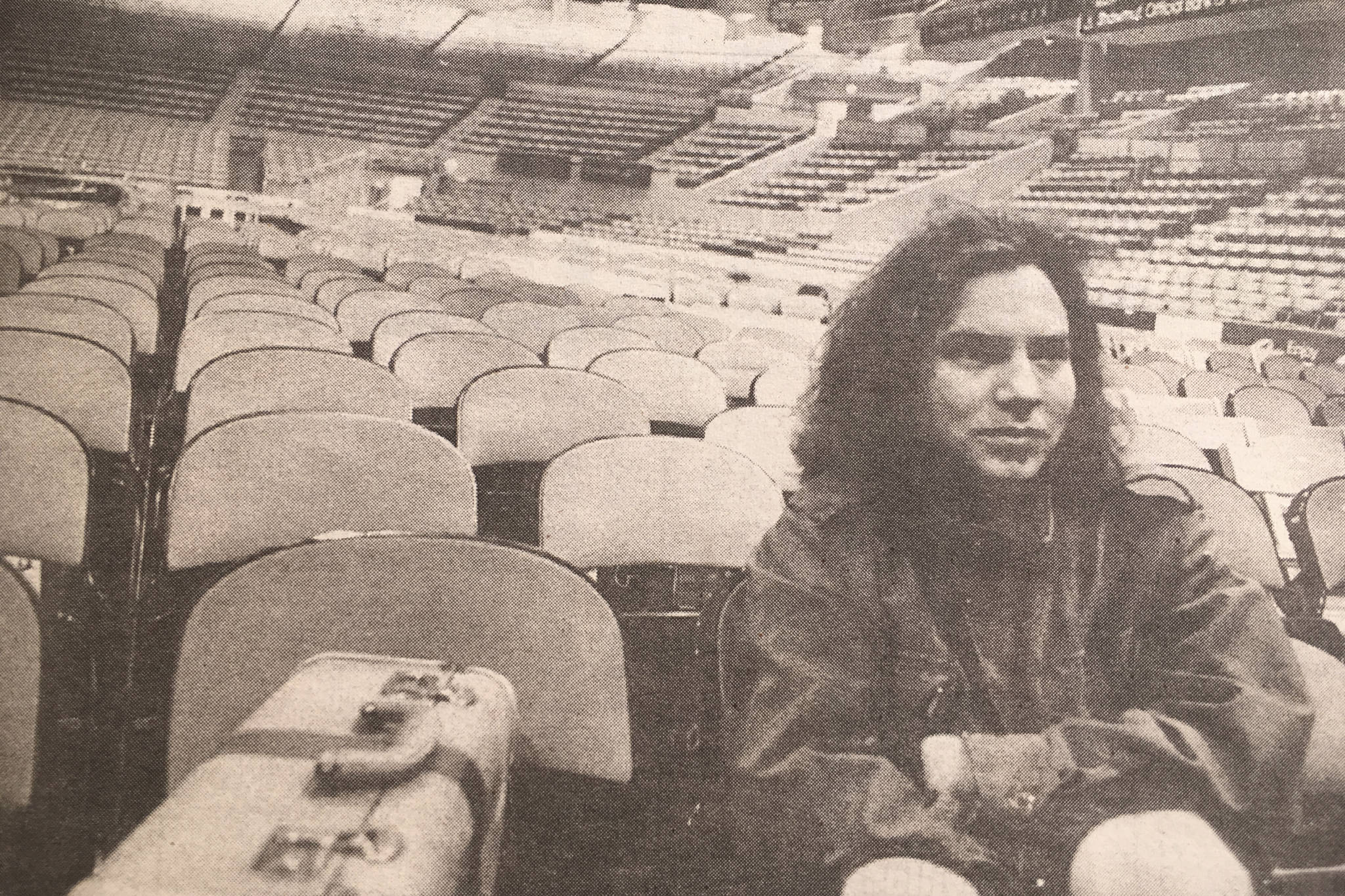

the kid by Dan Savage (Dutton, $22.95)

But then, as he listens to each couple introduce themselves and detail the complex nightmare they have endured while coming to terms with infertility, he discerns a familiar theme in the tales of their grief:

I sympathized with the straight people sitting around the conference table. I understood what they must have been going through. I had been through it myself, a long time ago. When I hit puberty, I got the news that I was functionally infertile. But the straight couples at the seminar had only recently gotten that news, and they were still adjusting to it. How much we had in common with them was driven home by the rhetoric the counselors used during the seminar. It was the rhetoric of coming out. The straight couples were encouraged to accept what they could not change. In time, they’d see their “problem” as a blessing. It was important to tell family and friends the truth, even if they might not understand at first. They might in their ignorance ask hurtful questions, but be patient and try to answer. And while it is possible to live a lie, possible to adopt a child and pass it off as your biological child, no one can spend a lifetime in the closet.

Now we all had some common ground.

Among the many oddities in this odd and remarkable book is this one: Of the scores of books on adoption in print at the moment, the best—most informative, most moving, most empathetic, and most instructive—is by a gay male who has made a career out of being outrageous and offensive to heterosexuals. Best known for an advice/humor column that runs in some 26 alternative newspapers (including New York’s Village Voice), Savage has produced a book that not only obliterates powerful negative stereotypes about homosexuals—it also obliterates powerful negative stereotypes about adoption. Much of the early attention of The Kid focuses on gay adoption issues; but the best material in the book has to do with adoption in general.

This is not to say that the sexual orientation of the Kid’s parents is not central to the book or that there are not enough invocations of cocksucking, shaved butt-cracks, and fisting to make some people stop reading. But it is to say that it is less central than the history and practice of what now is called “open adoption”—an arrangement by which a pregnant woman (“birth mother,” in adoption parlance) selects an adoptive family for the baby she intends to relinquish. The open adoption movement, which began some 20 years ago in reaction to draconian “closed” adoption practices, is now the predominant form of in-country adoption in the United States. Dan and Terry, then, were selected by a birth mother—a 20-year-old “gutter punk,” seven months pregnant, who lived on the streets of various cities and picked a gay couple because she thought the heterosexual couples she’d been offered were “phony.” Dan and Terry met frequently with her, force-feeding her steak through the last eight weeks of her pregnancy, and took great pains (far more than usual in open adoptions) to maintain contact with her and with the birth father after the adoption was finalized.

It goes without saying that this sort of adoption is an emotional roller coaster that all but defies description. Couples who have been trying for years to have children suddenly find themselves at the mercy of a mercurial teenager. At every turn, something threatens to derail the pending adoption, and no one knows how the pregnant girl will react to the baby once it is born. The drama is excruciating, to say the least.

In detailing his experience and mixing in general adoption information he learns from professionals along the way, Savage presents a primer on what to expect when you set out to adopt. He does an admirable job—as a source of information about the nuts and bolts and emotions of open adoptions, The Kid is a near-masterpiece.

There are, however, some editorial and factual anomalies. Savage writes that gay couples adopting Chinese infants (foreign adoption is far more widespread, and far easier, than in-country adoption) must be “discrete,” when he means “discreet.” He says that open adoption is legal in only three states, when in fact the practice is so common that for all practical purposes it is legal everywhere, although different states have different rules governing it. And readers might be misled by the ease with which the author and his boyfriend get their baby; most couples spend years trying to adopt, while Dan and Terry are parents within three months of applying—an unimaginably short journey.

Strangest of all is the assertion Savage passes along from an attorney friend that birth mothers relinquish children because they “have something they want to accomplish in life” while potential birth mothers who keep their babies tend to be “women with little to look forward to.” This is the sole lapse into stereotyping in The Kid. As is clear from his own experience with Melissa, the birth mother of his and Terry’s baby, the opposite is nearly always the case: Birth mothers relinquish because they cannot provide what they want their babies to have (often nothing more than a two-parent family); they make a heart-rending, utterly self-sacrificial decision to give their babies a better life. While no two birth mothers are exactly alike—just as no two adoption stories are exactly alike—the story Savage tells, with its moving portrait of his child’s birth mother, is much more representative of reality than the more stereotypical story he says he is going to tell.

These, though, are relatively minor failings. On balance, The Kid is an outstanding book on two subjects—homosexuality and adoption—that have long been shrouded in bigotry and misinformation.