For the past two years I have lived in Klahanie, a vast and meticulously planned Eastside development of 3,000 houses and apartments, 1,500 Grand Cherokees, 300 acres of mostly unmolested forest, and 45 pages of lawyerly rules governing what I may do with my house and keep on my property. Our rules—”Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions” (CC&Rs) in lawyerese—aren’t unusually chafing for a modern American subdivision. They don’t outlaw basketball hoops or doghouses (as long as Bowser’s condo is “compatible with the homeowner’s house in color and material”). But an item in the January homeowners association newsletter made me wonder what might be coming.

A “compliance committee” was forming, the newsletter reported, and encouraged us to sign up to work on it. “Volunteers would probably stroll neighborhoods looking in an unobtrusive manner for obvious CC&R violations.” The next newsletter’s report sounded a little less nonchalant. “We will begin this spring by touring our neighborhoods and appropriately tagging homeowners who violate the current rules and regulations.”

See end of article for related links.

I rewound to the development where I’d lived in Tucson, Arizona, before moving here. A retired colonel with an active ache for authority had appointed himself commissar of compliance, and he vigorously patrolled the neighborhood with a selection of threatening notices to post on miscreants’ cars and front doors. A volcano of resentment simmered, and the air at the annual association meetings was usually acrid with hostility.

I lived there for six years in violation of one of the rules. I operated a home business: I wrote books and magazine articles like this one in a cluttered office overlooking my front porch. Someone once brought it up. I bared my teeth and hissed that I would take it to court in a bloody instant, swaddled in the First Amendment. The City Council can’t dictate where a writer does his work, nor the state Legislature, nor Congress. Just let a neighborhood association try!

Klahanie appears a little more lenient; the rules say the association “may permit specified home occupations.” But I haven’t asked for permission, and after this story appears, it might be inclined not to give it. Nor am I so smug about my constitutional armor anymore. Neighborhood associations regulate all kinds of behavior that other governmental bodies either cannot (constitutionally) or dare not (politically). They are private governments, like corporations, which gives them reign over a wide range of things we used to believe were personal decisions—including who may and may not live on the property we own and what we do with and in our houses.

A lot of this has been well documented (most thoroughly in the 1994 book Privatopia, by lawyer and political science professor Evan McKenzie). What brought me into it for a fresh look was, first, the warning that my own house is about to be checked out—unobtrusively, I’m assured, by a strolling compliance committee; and then a nagging question: Why are we so casually giving up personal liberties and assigning police powers to these associations that we wouldn’t dream of letting any other government have?

No eggplant, no stucco

Homeowners associations are a booming industry. In 1970 there were about 10,000 scattered around the country; today there are 205,000. The Community Associations Institute (CAI) in Alexandria, Virginia, estimates that 6,000 to 8,000 new associations spring into being every year now, with 60 percent of all new urban housing falling under them. Litigation has become a lively activity; some law firms now specialize in writing CC&Rs and helping associations enforce them in court.

And American courts have increasingly endorsed the associations’ governmental powers. “Historically, there was a tremendous legal aversion to controlling what people do with their property,” says Kris Sundberg, a Mercer Island lawyer and president of the Washington CAI chapter. “This went all the way back to English common law.” But as the Washington State Supreme Court affirmed in a 1997 case, “Modern courts have recognized the necessity of enforcing such restrictions to protect the public and private property owners from the increased pressures of urbanization.”

Sundberg, who says he is philosophically a libertarian, is nonetheless a friend of homeowners associations and their rules. First, he says, we’re all free to live wherever we want—the fact that 60 percent of all new urban housing comes wrapped in covenants means that 40 percent does not. And second, he says, “The overwhelming majority of people who live in covenant-restricted communities are perfectly happy with the arrangement. The fact that there are occasional problems should not be construed as a condemnation of the concept.”

That’s probably true. Until one gets involved in the occasional problem. There’s an increasingly rich lore of astonishing cases—some tragic, some absurd, and most, because they usually involve lawyers, very expensive for someone.

In New Jersey, an association sued a 60-year-old resident who had taken a 45-year-old bride, three years too young for the community’s age restriction. The association won, and the court ordered the husband to sell the home, rent it out, or live separately from his wife.

In Santa Ana, California, a condominium association posted a notice by the mailboxes accusing a resident of “parking in [a] circular driveway… kissing and doing bad things for over one hour.” The “bad things” weren’t spelled out, but the accused, a 51-year-old grandmother, was plenty livid. She won an apology only after the story made the Los Angeles Times and USA Today.

In the Fort Lauderdale, Florida, suburb of Tamarac two years ago, a homeowner decorated her property for Halloween, planting foam gravestones in the lawn and hanging swaying ghosts from the eaves and masks in the trees. Her association fired off a letter insisting that this was not an allowable holiday for decorations. “Christmas, Chanukah, and New Years have traditionally been known as THE HOLIDAYS,” it said. “This is the time of year we can tastefully proclaim who we are and what we stand for. Conversely, Halloween, Easter, Columbus Day, Valentine’s Day, and any others… can not be equaled to THE HOLIDAYS.”

Seattle and its suburbs are well back of the cutting edge of homeowner-association disputes (the nastiest cases routinely turn up in California and Florida), but trouble does arise here. A friend in the Horizon Crest neighborhood of Bellevue currently is mulling a demand that he trim two tall fir trees behind his house. The CC&Rs say that trees and shrubs shall not be permitted to block the views from other houses, “except for existing trees of exceptional beauty.” He sniffs a tantalizing vagueness in the wording and is stiffening for a fight. “I hereby declare these to be existing trees of exceptional beauty,” he told me.

But the fight might not be a lot of fun. In 1992, a Medina couple named William and Carolyn Riss bought a Clyde Hill lot with a knock-downer and drew up plans to build a new house for themselves. The homeowners association denied permission because of the house’s proposed size, siting, and stucco finish. The Risses sued. To make a five-year-long story short, the Risses built the house, fought the association all the way to the state Supreme Court, and finally won. “I was so nervous and distraught I had to stop work for several months,” Carolyn Riss recalls. “I had migraines. My husband said he wouldn’t live in that neighborhood even if we could have built the house for free. We put it on the market, and it took about a year and a half to sell it.”

Eastsiders still shake their heads in amazement at the Lee and Barbara Jones case in the English Hill neighborhood. In 1991 the Joneses painted their neo-Victorian house mauve with eggplant and teal trim, neglecting to ask the association for permission first. Real Victorian homes often sported exuberant color schemes, but modern imitations are, well, pale in more ways than one. The association sued, and after a two-year fight, forced them to repaint the house and pay all the legal bills. “It cost—besides all the bad blood in the neighborhood—about $68,000,” Lee Jones says. They had to refinance the house, he says, and suffered “an unbelievable strain on our family.”

And yet the anecdotes trivialize the issues underlying them. Why are we struggling so mightily to control our neighbors, and what effect is it having on our communities?

Suburban Gestapo

Neighborhood governments and CC&Rs—they used to be called simply “deed restrictions”—are as old as 18th-century Williamsburg, where houses had to “come to within six foot of the street, and not nearer,” and be fenced “with a wall, pails, or post and rails.” The reason was to create a physical sense of community and to impose an orderly human rhythm on nature-paired impulses that have had everything to do with American city building of the last 300 years.

In the 19th century, primordial developers began to attach “restrictive covenants” to luxury neighborhoods such as New York’s Gramercy Park. At first they simply guaranteed the residential character of the neighborhood (zoning

didn’t dawn in American cities until 1916), but a few generations later, when folk of color began laddering into the middle class, covenants were used to keep neighborhoods white, typically forbidding anyone of the “African or Asiatic race,” among others, to buy property.

In the landmark 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer case the US Supreme Court struck down race-related covenants, but then new kinds of restrictions arose. Retirement communities with age cutoffs—50, 55, 60—sprang up in the Sunbelt. They did not become known for neighborly tolerance. A child would be orphaned by an accident, the grandparents would take him in, and then the neighborhood association would force them to move. Lawyers always advised that if the community were to grant an exception or look the other way, then it would lose its power to enforce the covenants in the future.

Developers and the associations that follow them also have waded into the arena of behavior control, and not just around the community swimming pool. Some condo associations maintain a blackout on pets of all kinds, including goldfish and parakeets. Some specify the maximum number of nights that guests may stay. In Phoenix, Charles Keating slipped in a rule banning “pornographic” films, books, magazines, and devices from the homes in Estrella, his star development. (Keating was later convicted of securities fraud and sentenced to 10 years in prison; in February the conviction was overturned and sent back for retrial.)

The classic rationale for CC&Rs is that they preserve property values by forcing everyone in the neighborhood to maintain their houses and yards and not do anything rebarbative. And they protect everyone against obvious nuisances, such as a backyard kennel operation or a hobbyist’s iron foundry in a garage. This ensures a denominator of predictability, which Mercer Island’s Sundberg says Americans crave. “I think it’s the same reason that when you’re on a road trip, you stop for lunch at McDonald’s or Burger King as opposed to some independent hamburger joint. There’s a consistency of product. In a homeowners association, you have the expectation that the look of the community is going to be maintained over your period of ownership.”

I called David Demmon, who heads my own association’s nascent compliance committee. He sounded amiable and perfectly reasonable, and explained that the strolling volunteers—so far—are focusing on just two violations: holiday decorations, which are supposed to be taken down no more than 30 days after the holiday; and trash cans, which are welcome outside only on the day of collection. I asked why he had volunteered for the committee. “My wife and I have lived in Klahanie for six years, we enjoy it very much, and felt this was something we could do that would benefit the neighborhood.”

But I also interviewed Kerry Wyman, executive vice president of a condominium management company in Bellevue, who has seen too many associations where people fixate on minutiae. “Sometimes you get people on a power trip—maybe people who never had power before, and who are now using that power to make everyone’s life miserable. There are communities where it’s like the Gestapo, with people actively pursuing violators. These don’t even function as neighborhoods. They create their own problems by going after people.”

Wyman lives in Lakemont, an upper-middle-class Bellevue neighborhood of steep hills and relentlessly taupe homes. There’s no Gestapo about, but there is a lot of silliness. She points out a neighbor’s fence. “They had to tear out their fence and put this whole new one up because the posts didn’t have these little required decorative cubes. Another neighbor wanted to paint her front door forest green. It became a huge deal in the association. The color of a door isn’t going to affect your property value. Maintenance will. That’s what should be the issue.”

I ask Wyman if it’s just that we fear eccentricity. She looks bemused. “We’ve come to the point where a green door is eccentric?”

Neighbors just like me

As Einstein said in a different context, “Something deeply hidden had to be behind things.” We give up a galaxy of rights and open ourselves to a lot of potential unpleasantness when we join a neighborhood association, and a hunger for reliably bland hamburgers doesn’t explain it.

First, let’s look at the obvious. Homeowners associations are largely creatures of the suburbs, and suburban development today is growing just as dense as the cities that people began scurrying out of in the 1950s. When you can stretch out on an acre of pasture, it’s fairly easy to ignore your neighbor if you choose to. When houses are squeezed together like olives, six or eight to the acre, the social pressures for conformity and behavior control multiply correspondingly.

Next, let’s quit kidding ourselves. Whatever their liberal blathering, most people feel most secure when they live around people a lot like themselves.

Covenants can’t create ethnic segregation anymore, but they can and blatantly do foster class segregation. Many common CC&Rs have an anti-blue-collar air about them, such as prohibitions against chain-link fences and pickup trucks with campers or commercial signs (“Joe Bob’s Plumbing”) on them. Many affluent developments require all new houses to be of a minimum size and may even specify a minimum allowable construction cost.

Alongside social homogeneity, “People feel a need for consistency and visual harmony,” says Philip Langdon, author of A Better Place to Live: Reshaping the American Suburb. “They wish for things to fit together. They yearn for coherence.”

In America this impulse traces back at least to Thomas Jefferson, who raided classical Rome for the architectural style he felt fit for a budding nation. It’s routinely supposed that Jefferson advocated Roman architecture because it made a convenient and elegant symbol of democracy, but he was actually more concerned with imposing a rational, humanistic order on the messy natural landscape. This is exactly what we’ve been trying to do with our suburban housing developments for the last 50 years, although it’s hard to imagine Jefferson being very happy about them.

There are so many things in contemporary life that are beyond our control—technology, the economy, our job security, our kids’ safety at junior high school—that we’ve come to embrace the facade of order in our neighborhoods, which neighborhood associations and their CC&Rs preserve. It’s no coincidence that some of the most tightly controlled communities are achingly “traditional” in appearance—most notably the new Disney community of Celebration, Florida, where the houses come in six historical flavors and any alteration, even the color of window shades seen from the street, must be approved in writing. The web of rules is designed to maintain the comforting fiction of an old-fashioned town in an earlier, simpler time, before TV, Internet sex, and snipers in the neighborhood school yard. Since we can’t manage the furies simmering below the surface, we control the symbols immediately around us so that they’re reassuring—and unchanging.

The last two houses I’ve lived in have been in covenant-controlled developments, where the architectural monotony of the neighborhood quickly fatigued me. Why, given my healthy disrespect for authority, did I buy in such places? I’ve told people it was for the scenery nearby, or the nice, high ceilings. But I’ve been in denial. Fear? Probably. Neighborhoods like these tell you that you know what to expect, even though underneath, you know it’s a flimsy deception.

Fear is a very big part of the reason we’ve become a nation of suburbs. Fear of integration, fear of crime, fear of political and social instability, and arching over all, the fear of losing control of our immediate circumstances. These fears don’t go away in the suburbs, but they are easier to suppress. The surface is calm, the houses are pastel, there’s nothing to worry about. If all the houses look just like mine, well, all the people in them must be just as nice and rational as me—right?

“All human communities involve an intense interplay between the individual and the law,” writes Vincent Scully, the architecture historian who has made a good career of thinking deeply about architecture’s social meaning. “Without the law there is no peace in the community and no freedom for the individual to live without fear. Architecture is the perfect image of that state of affairs.”

The problem with the image staged and enforced by homeowners association law—and it goes deeper than the occasional spats and lawsuits—is that it creates communities of mind-numbing sterility and banality.

Americans feel vaguely unfulfilled by modern neighborhood development, that it lacks a sense of real community. Since the rise of the “new urbanism” movement in the late 1980s we’ve been trying to fix it with a return to some of the cherished symbols of generations past, such as narrower, pedestrian-oriented streets, big front porches, and retail clusters in walking distance.

The problem is that this is master-planned picturesqueness, a vision that springs fully formed from a developer’s mind and lives on in the covenants. A real community is a living organism, constantly evolving and reflecting the ideals and messiness and eccentricities of the people living in it.

It fakes a village

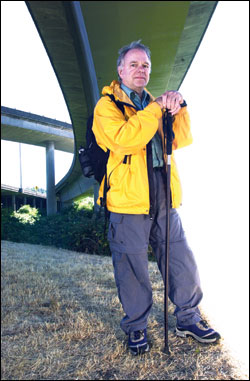

“It’s a tough balancing act,” says Judd Kirk, president of Port Blakely Communities, which is responsible for the new-urbanist Issaquah Highlands development (the project formerly known as Grand Ridge). “What are the things you want to control, and what do you want to just let happen?”

Kirk, a slim man with short, silvering hair and an office bookshelf that includes books critiquing modern development, appears to have spent some quality time pondering a developer’s responsibilities in creating community. Developers have to do it, he says, because homeowners today don’t have the time. Community doesn’t just happen in the 1990s, not when the kids are bused to schools 10 miles away and the parents radiate to workplaces 20 or 50 miles away. But if a developer creates an infrastructure—neighborhood parks, gathering places, an electronic community web—then, he believes, people will take advantage and build on it.

It takes 15 minutes for Kirk’s receptionist to make me an unabridged copy of Issaquah Highlands’ CC&Rs, and the package does not make exciting bedtime reading. It does nod toward a new, and, I think, enlightened direction in neighborhood government. “Standards for use and conduct, maintenance and architecture within Issaquah Highlands are what give the community its identity and make it a place that people want to call ‘home,'” it says. “Yet those standards must be more than a static recitation of ‘thou shalt not’s’… ” It goes on to set up procedures for rule-making that, theoretically, can evolve with time, technology, and changes in society.

“We want to have mediation instead of control,” Kirk says. “For example, the question has come up, will we allow basketball hoops? Of course we’ll allow them. Probably 2 percent will cause problems—some kids will play late at night, and that’ll keep someone awake. And then we’ll deal with that.”

What Issaquah Highlands doesn’t address is the long-term effects of neighborhood government, which a few critics have begun to think about. There will be an architectural review committee, and the CC&Rs give it absolute authority: “Decisions may be based on purely aesthetic considerations… [and] each Owner acknowledges that determinations as to such matters are purely subjective.” So if the committee members happen not to like deconstructivist architecture or eggplant-colored trim, well, it won’t be allowed.

In A Better Place to Live, Langdon wrote, “I know of no studies of the effects of homeowners’ associations on children, but logic suggests that associations with intrusive rules diminish children’s independence and self-reliance. Children learn by watching adults. When they see the adults being told what color to paint their house, which tones of basketball backboards to buy, and where not to plant a garden, children can hardly avoid concluding that the scope of individual action in contemporary America is narrow indeed.”

Richard Louv echoes the thought in Childhood’s Future: Listening to the American Family. “What’s been forgotten is that it is our culture that is being shaped, not just housing…. We have a generation in this country that doesn’t know you should be able to paint your house any color you want.”

The flowering of diversity in our environment has an effect on the way we ultimately come to see the world, and on our capacity to think creatively. This isn’t an argument for encouraging chaos or squalor—few people want to live next door to Dogpatch—but it is one for an environment of inclusion rather than exclusion. Old neighborhoods in Seattle are stimulating because no one could stop things from happening, whether by whim or genius. Fifty years from now, if neighborhood associations still govern as they do today, the sprawling neighborhoods of the Eastside will have exactly as much character and soul as they do today.

Related Links:

Klahanie page: A planned community in Issaquah

Thoughts on utopian villages

http://www.zingmagazine.com/zing3/

ritchie/brackman.html

Community Associations Institute homepage

http://www.caionline.org/home.htm

You tell us: Should your neighbors have a say in how you keep your yard?